Using census records

When I ponder about the history of our French water mill, I guess one of the things that immediately comes to mind is the people who lived and worked here. One of the old post cards that I had managed to find shows a couple standing outside the mill.

The figures are very tiny and you can’t make out any detail but chances are they are the miller and his wife. The post card dates back to about 1915 and the photograph is probably not much older.

I decided to see if I could find out anything about them, but as we were in full Coronavirus lockdown at the time and could only leave the house for essential shopping with a signed form, everything would need to be done online.

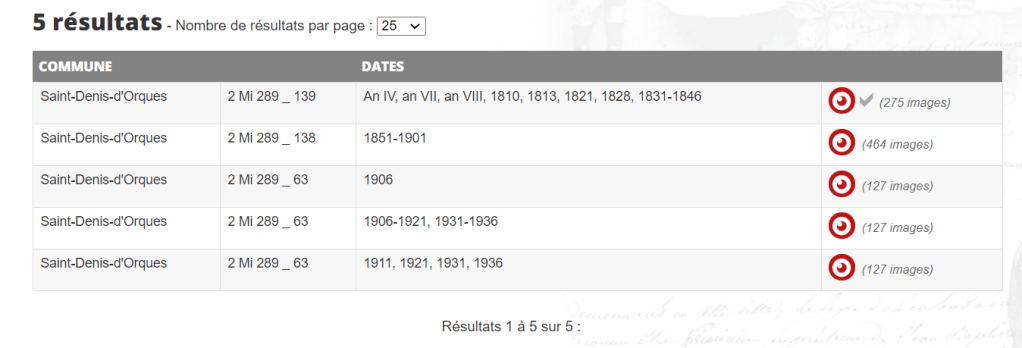

Not having any names or even a definite year I decided to look for census records. I googled ‘archives Sarthe’ (our department) and found the departmental archive website, http://archives.sarthe.fr/. Each department has its own site and they are all slightly different, with varying amounts of information, but you should definitely find census returns, (Listes nominatives de recensement de population).

You should be able to filter on the name of your commune. Then just pick the document with the year you want and you’re off!

If your commune’s census records go back to late 18th/early 19th century you will probably find the year referred to according to the Republican calendar, when the French basically started afresh and invented a new way of counting the days, months and years. So if, for example, you see ‘An VII’, it’s referring to Year 7 of the new Republican calendar. Convertion tools can be found by googling or clicking here.

You may be lucky and find that your local archive also offers a base nominative, where you can search by a person’s name or a street name. Mine didn’t – down to pure slog then. You’ll also probably find that there are several different years’ census records in a single online document. I found it useful to make a note of the page number for the start of each year, because I inevitably need to revisit a particular year.

The pages are arranged slightly differently as the years go by, but you will see a column for Désignation, the location of the property first. A word of warning here, the numbers do not refer to the number of your house but the register numbers for areas, households and people. House numbers in towns are a relatively recent innovation. If you live in a rural property with a name you will find it much easier. If you are in a village or town, try looking at the order the roads run in or look for identifiable buildings like large important houses with names or presbyteres and work back from those.

There is no getting away from it – it is time consuming, but not difficult. Clusters of houses may once have been separate from the village and could be designated as a hameau – in one census le Moulin de la Roche is lumped in together with Hameau de la Roche, while in others it is recorded separately. In a larger group of homes ( eg a hamlet or large farm) the members of an individual household are bracketed together; useful for identifying servants etc.

The information given is normally

- Family name: women are often recorded using their maiden name as this is their legal name in France.

- Given names: it is very common to find several generations of members of the family registered with the same first name. To avoid confusion, they were then often know by their second or third given name!

- Date of birth: very important for finding them in other registers and resources

- Place of birth: The full name of the village may not be given. Rosalie Joubert, in my snapshot of the Joubert family, is shown as having been born in Saint Ouen, but there are 4 villages in the area call Saint-Ouen-something!

- Nationality: as this would usually be français, it is often marked with ‘I’ or ‘Id’ meaning ‘idem/ditto/same as above’

- Relationship to the head of the household: chef or chef de ménage meaning head of the household not the cook! For example: Épouse = wife, fille-daughter, fils=son, belle-fille= step daughter but can be daughter-in law (age usually helps to work out which) beau-fils= step son/son in law, domestique=maid

- Profession: job. (S.P. = sans profession, often used for wives, children and elderly relatives.)

- In the last column in this example it says if the person is the boss, business owner or a home worker to put Patron and if an employee to write the name of the employer they work for.

Using the census lists will give you some names and dates to start you off on your sleuthing. It’s really interesting to see how households changed over the years. You often find children named on one census who are missing in the next. A quick check of their age at the time (Anything from 12 onwards depending on the century) might then suggest they had left home to go into service in another house or to seek work in another village. Of course it could also point to an untimely death, as child mortality rates were so much higher. In the Joubert’s case, the disappearance of son Robert was later explained by finding him living with a wet-nurse.

To see the kind of information I was able to find on the miller at Moulin de la Roche during the Great War, click the link below.

1902-1918

or click on ‘History’ in the menu at the top of the page.

If you have had a go starting to research the history of your home, please do leave a comment and let me know how you got on – particulary if you have any tips you can pass on!

You might also be interested in:

Absolutely fascinating, but very time consuming. part of our house dates back to 1060 and was a fort it would great to find any military records.

LikeLike

That’s amazing! It’s so exciting to think there are so many stories behind where you live. How did you find out that date?

LikeLike